I have a new novel that has just this past month been published in paperback. The Betrothed Sister is about the marriage between Gita, King Harold of England's daughter and a Prince of Kiev during the latter half of the eleventh century. I am writing a new book. My work in progress will be concerned with a woman from the early Tudor merchant class. The heroine is a widow. She has a wonderful story.

There is a question over when the medieval period ends. Some historians, myself amongst these, believe that the medieval period really ends in England with the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. I actually believe it ends even later, around the mid sixteenth century, certainly not with The Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

A story set circa 1512 is, to my mind, a late medieval story. England was still Catholic. The monasteries basked contentedly for the most part amongst England's rivers and in towns and the countryside. Cathedrals with beautiful carvings, stained glass and great spires reached heaven-wards. The landscape of London looked much as it did in the previous century with a busy River Thames, medieval buildings, wood with tiled roofs and overhangs and many monasteries and churches. It is a delightful world to set a novel in, though, of course it has its underbelly. Life could be short, life could be hard and women struggled to find a voice, never mind any degree of independence.

There were strong women in trade throughout the medieval and Tudor period. There were some women who achieved independence by amassing fortunes. These female merchants were, for the most part, widows. The Wife of Bath was one such lady.

In the late medieval era the term merchant sometimes meant a man or woman of mixed enterprise. Although he or she might have a dominant particular trade, the merchant often combined this with a number of other interests. Mercers, for example, traded in fine textiles. Grocers traded in spices. My lady trades in cloth, gorgeous cloths. Whilst a merchant might trade in wool and cloth they were often ready to deal in any other merchandise that came their way. Mercers often derived a considerable profit from a retail business in luxury fabrics. My protagonist, for example, is anxious to get her hands on a variety of what was known in 1512 as New Draperies, fabrics that consisted of long combed out woollen threads mixed with silk or linen so that they were light textured. Cyprus gold thread might be sold alongside lace from Venice even though the merchant's stock also included good English products such as Cornish blanket cloth, London silk, Bury napery, stained or painted cloths and fine linen towels.

Merchant companies did have a few associated female members. They also divided their membership into those who were entitled to wear official clothing or livery in company colours and those who were not. The group excluded from livery were mixed. Some never succeeded in launching themselves into wholesale trade. This group depended on retail shopkeeping for their living. In all merchant companies there would be a group of young men, called yeomen, with capital and influence who were prepared to enter the livery. First they must serve under an older merchant to gain experience. Hopefully, later they could set up in business independently. Around the age of thirty they might be accepted into the livery.

Livery men discussed company affairs in quarterly meetings. The yeomanry or rather these young trainees did not attend. Young merchants in service were similar to poorer shopkeepers. The companies were well established by 1512. By the fifteenth century they had acquired pleasant halls that served as club premises as well as administrative headquarters. Members dined apart from the yeomen at quarterly dinners. They threw lavish entertainments for friends and patrons such as lawyers and noblemen and government officials.

As well as companies there were also the fraternities. Fraternities were Parish based. They looked after the church and the poor. They collected alms to help members in trouble and elected wardens to run the show. They had annual banquets and processions. For example the skinners liverymen organised a solemn procession on the feast of Corpus Christi to which their fraternity was dedicated. The fraternities could have members from outside the company. I think they were more diverse and colourful and more inclusive. Often the trades belonged to both, their company and a fraternity. The fraternity might include shear men, pewterers, bakers and so on. To give an example, the Fraternity of St Katherine at St Mary Colechurch in Cheap was supported by ironmongers, drapers and armourers amongst others.

The Gild was a third kind of organisation. Gild regulations expressly excluded women from participation in a trade but they made exceptions for wives and daughters. Wives assisted their husbands in his trade, and, as pointed out already, a large number of widows carried on their dead husband's trade. Sometimes gild regulations allowed them to do so. There is strong evidence for this because men often stated in their will that their apprentices should serve out their term with the widow. They often left widows implements belonging to their trade. Trades carried out by women ranged from that of merchants on a large scale trafficking in ships and dealing with the crown to that of small craftsmen/women. Even as far back as The Hundred Rolls of 1274 there is mention of the great wool merchants of London widows who make a great trade in wool and other things. At least one woman is referred to in lists as a Merchant of the Staple, an exporter of wool to Calais.

Here is an interesting fact to finish on before I go back to working on my new novel. Girls were often apprenticed to trades the same way as boys. A father in an urban occupation will leave a daughter money in his will to wed her or he will leave the money to put her in trade!

Women may have been the footnotes of history. It was often the aristocratic women who might just get a line or two. However, just like Gita from The Betrothed Sister and my merchant widow in my WIP, women had more power than we often realise back in the Medieval period.

|

| Gita, Daughter of King Harold |

There is a question over when the medieval period ends. Some historians, myself amongst these, believe that the medieval period really ends in England with the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. I actually believe it ends even later, around the mid sixteenth century, certainly not with The Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

A story set circa 1512 is, to my mind, a late medieval story. England was still Catholic. The monasteries basked contentedly for the most part amongst England's rivers and in towns and the countryside. Cathedrals with beautiful carvings, stained glass and great spires reached heaven-wards. The landscape of London looked much as it did in the previous century with a busy River Thames, medieval buildings, wood with tiled roofs and overhangs and many monasteries and churches. It is a delightful world to set a novel in, though, of course it has its underbelly. Life could be short, life could be hard and women struggled to find a voice, never mind any degree of independence.

| Medieval towns where the Church dominated the landscape |

There were strong women in trade throughout the medieval and Tudor period. There were some women who achieved independence by amassing fortunes. These female merchants were, for the most part, widows. The Wife of Bath was one such lady.

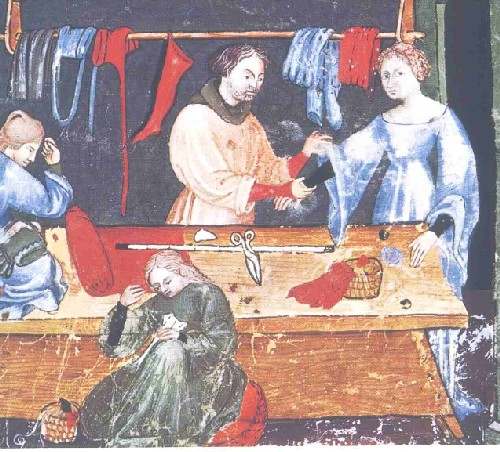

In the late medieval era the term merchant sometimes meant a man or woman of mixed enterprise. Although he or she might have a dominant particular trade, the merchant often combined this with a number of other interests. Mercers, for example, traded in fine textiles. Grocers traded in spices. My lady trades in cloth, gorgeous cloths. Whilst a merchant might trade in wool and cloth they were often ready to deal in any other merchandise that came their way. Mercers often derived a considerable profit from a retail business in luxury fabrics. My protagonist, for example, is anxious to get her hands on a variety of what was known in 1512 as New Draperies, fabrics that consisted of long combed out woollen threads mixed with silk or linen so that they were light textured. Cyprus gold thread might be sold alongside lace from Venice even though the merchant's stock also included good English products such as Cornish blanket cloth, London silk, Bury napery, stained or painted cloths and fine linen towels.

|

| When cloth was king |

Merchant companies did have a few associated female members. They also divided their membership into those who were entitled to wear official clothing or livery in company colours and those who were not. The group excluded from livery were mixed. Some never succeeded in launching themselves into wholesale trade. This group depended on retail shopkeeping for their living. In all merchant companies there would be a group of young men, called yeomen, with capital and influence who were prepared to enter the livery. First they must serve under an older merchant to gain experience. Hopefully, later they could set up in business independently. Around the age of thirty they might be accepted into the livery.

|

| A busy merchant's workshop |

Livery men discussed company affairs in quarterly meetings. The yeomanry or rather these young trainees did not attend. Young merchants in service were similar to poorer shopkeepers. The companies were well established by 1512. By the fifteenth century they had acquired pleasant halls that served as club premises as well as administrative headquarters. Members dined apart from the yeomen at quarterly dinners. They threw lavish entertainments for friends and patrons such as lawyers and noblemen and government officials.

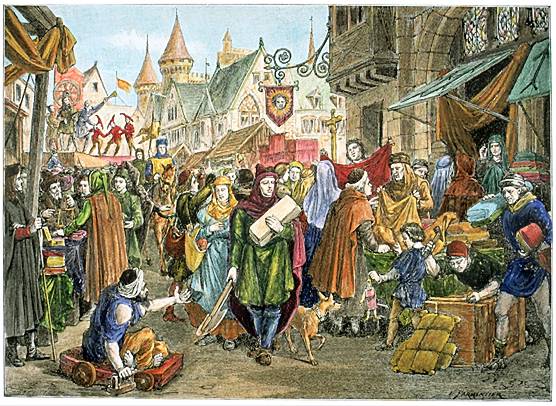

As well as companies there were also the fraternities. Fraternities were Parish based. They looked after the church and the poor. They collected alms to help members in trouble and elected wardens to run the show. They had annual banquets and processions. For example the skinners liverymen organised a solemn procession on the feast of Corpus Christi to which their fraternity was dedicated. The fraternities could have members from outside the company. I think they were more diverse and colourful and more inclusive. Often the trades belonged to both, their company and a fraternity. The fraternity might include shear men, pewterers, bakers and so on. To give an example, the Fraternity of St Katherine at St Mary Colechurch in Cheap was supported by ironmongers, drapers and armourers amongst others.

|

| The busy medieval street |

The Gild was a third kind of organisation. Gild regulations expressly excluded women from participation in a trade but they made exceptions for wives and daughters. Wives assisted their husbands in his trade, and, as pointed out already, a large number of widows carried on their dead husband's trade. Sometimes gild regulations allowed them to do so. There is strong evidence for this because men often stated in their will that their apprentices should serve out their term with the widow. They often left widows implements belonging to their trade. Trades carried out by women ranged from that of merchants on a large scale trafficking in ships and dealing with the crown to that of small craftsmen/women. Even as far back as The Hundred Rolls of 1274 there is mention of the great wool merchants of London widows who make a great trade in wool and other things. At least one woman is referred to in lists as a Merchant of the Staple, an exporter of wool to Calais.

|

| Norwich was a town involved with the Staple |

Here is an interesting fact to finish on before I go back to working on my new novel. Girls were often apprenticed to trades the same way as boys. A father in an urban occupation will leave a daughter money in his will to wed her or he will leave the money to put her in trade!

|

| Women in the cloth trade |

Women may have been the footnotes of history. It was often the aristocratic women who might just get a line or two. However, just like Gita from The Betrothed Sister and my merchant widow in my WIP, women had more power than we often realise back in the Medieval period.