When did the medieval period in London begin and end? We assume that the medieval period began in England when the Romans departed circa 410 AD. However for the previous one hundred years the Romans had been withdrawing from England and they were using Saxon mercenaries to supplement the Roman army's reduced presence. The country continued to trade with the Empire. There was not a particular moment of change but the beginning of a reversion gradually to life as it had been prior to Roman occupation. This was the beginning of medieval England.

Society did not suddenly change in 1485 when the first Tudor king, Henry VII succeeded to the throne after The Battle of Bosworth. Nothing much actually changed until the mid 1530s when the monasteries were dissolved and the English Church was reformed. These were events that did cause great social upheavals. This was the end of medieval England.

Medieval London was contained within a semi circular wall that was interrupted by in order west to east, Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopgate and Aldgate just north of The Tower of London. The River Thames ran from east to west completing the semi circle.

My latest novel The Woman in the Shadows is set in London between 1514 and 1525. London is still a medieval city throughout the scope of this novel. London, itself, was a city of churches. It contained a greater number than any other city in Europe. There were more than a hundred churches within the walls of the old city. Sixteen of them were devoted to St Mary. The Church remained the single most disciplined and authoritative director of London's affairs until the Reformation. Church administrators were the biggest landlords and employers within and without the city walls. The city's saint was a seventh century monk who had ruled as bishop of London, Erkenwald. Even in the early sixteenth century the shrine of St Erkenwald was an object of pilgrimage to the successful lawyers of London. When they were nominated as serjeants of law they would walk in procession to St Paul's to venerate the saint.

Daily life was marked by the ringing of bells that rang from the churches and monasteries marking the religious offices. The most important bells were the Angelus Bells. The Angelus was associated with the worship of the Virgin Mary. The bell was struck to remind busy citizens to pause their work at midday to repeat the angelus, a triple hail Mary beginning with the words 'Angelus Domini Nunavit Mariae', 'The Angel of the Lord said to Mary.' In fact, the Angelus became the best way to tell the time because it rang at Prime, six o'clock, midday which was Sext and six in the evening for Compline. It was different to other bells because it tolled nine strokes at three times keeping the space of The Lord's Prayer, the Pater, and an Ave between each tolling. So if you lived on a late medieval London Street you would constantly hear bells ringing. The bells of the church tolled the end of each trading day. There was a bell that rang at dawn so the city gates would be opened and one that rang around six in the evening in winter and ten in the summer for the curfew to begin. After curfew Londoners had to carry a lighted torch or they could be arrested and incarcerated until dawn.

All over the city. my characters would hear a constant din from the different crafts that were practised. The noisiest were metalworkers; the blacksmiths, farriers, pewterers, silver and goldsmiths, cutlers and bell founder all used hammers and contributed to the general clamour. I can only compare the activity to that of busy streets in an Indian city or in cities of the Far East.

In London there were two hundred fraternities in which craft regulation and religious observation were mingled. Guilds had acquired enormous economic power within the city by the end of the medieval period. The growth of craft guilds in medieval London cannot be distinguished from the parish guilds of the same neighbourhood. thus tanners who worked along the banks of The River Fleet for instance would meet at their fraternity in the Carmelite house in Fleet Street. According to Peter Ackroyd in his book London, three fraternities were recorded at in the church of St Stephen, Coleman Street during the late thirteenth century. By the early fourteenth century only citizens could belong to a trade guild. Aliens were not only foreigners but those who were not London's citizens.

Many tradesmen met for business in the church. Religious and social constraints emphasized the importance of honesty and good behaviour. The guilds had their rules. Good names must be protected and the guilds condemned those who broke public peace. It was as if the act of quarreling or being involved in disputes might be construed as sinful.

Young people entered apprenticeships in late medieval London able to read and write. They were expected to be honest and to have learned manners. They were to be straight-limbed and free-born. And by the mid fifteenth century the children had to be born in England. Well-born recruits were preferred and parents of apprentices had to have properties bringing in 20s a year. The Lord's daughter, the baker's son, the children of London mercers, vintners or fishmongers were not raised at home for long. All of them were either apprenticed or they became attendants or servants in someone else's household. The best upbringing for a child was to send him out of the family to learn the ways of the world and to be educated elsewhere. Young women were usually apprenticed to silkwomen, dressmakers or embroiderers. There are instances too of girls being apprenticed to butchers, bakers, cordwainers, drapers, grocers, apothecaries and surgeons. They could either remain single and practise as femme soles under London law after they married and actually having a skill was an advantage in the marriage market. The apprentice term would end if marriage were offered and often the apprenticeship was only for four years, not seven, in practise although it was not legal. What a woman's apprenticeship was not, was as a stepping stone to an independent life as a citizen of London.

|

| Roman London |

Society did not suddenly change in 1485 when the first Tudor king, Henry VII succeeded to the throne after The Battle of Bosworth. Nothing much actually changed until the mid 1530s when the monasteries were dissolved and the English Church was reformed. These were events that did cause great social upheavals. This was the end of medieval England.

Medieval London was contained within a semi circular wall that was interrupted by in order west to east, Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopgate and Aldgate just north of The Tower of London. The River Thames ran from east to west completing the semi circle.

| Fourteenth Century Tower of London |

My latest novel The Woman in the Shadows is set in London between 1514 and 1525. London is still a medieval city throughout the scope of this novel. London, itself, was a city of churches. It contained a greater number than any other city in Europe. There were more than a hundred churches within the walls of the old city. Sixteen of them were devoted to St Mary. The Church remained the single most disciplined and authoritative director of London's affairs until the Reformation. Church administrators were the biggest landlords and employers within and without the city walls. The city's saint was a seventh century monk who had ruled as bishop of London, Erkenwald. Even in the early sixteenth century the shrine of St Erkenwald was an object of pilgrimage to the successful lawyers of London. When they were nominated as serjeants of law they would walk in procession to St Paul's to venerate the saint.

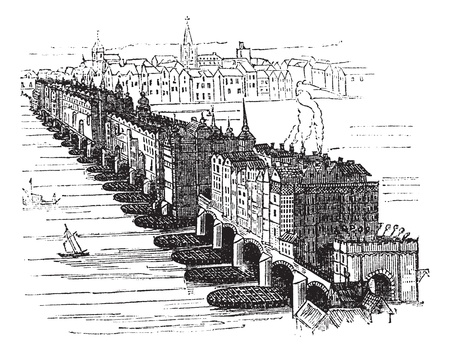

|

| Medieval London Bridge with shops, businesses and churches |

Daily life was marked by the ringing of bells that rang from the churches and monasteries marking the religious offices. The most important bells were the Angelus Bells. The Angelus was associated with the worship of the Virgin Mary. The bell was struck to remind busy citizens to pause their work at midday to repeat the angelus, a triple hail Mary beginning with the words 'Angelus Domini Nunavit Mariae', 'The Angel of the Lord said to Mary.' In fact, the Angelus became the best way to tell the time because it rang at Prime, six o'clock, midday which was Sext and six in the evening for Compline. It was different to other bells because it tolled nine strokes at three times keeping the space of The Lord's Prayer, the Pater, and an Ave between each tolling. So if you lived on a late medieval London Street you would constantly hear bells ringing. The bells of the church tolled the end of each trading day. There was a bell that rang at dawn so the city gates would be opened and one that rang around six in the evening in winter and ten in the summer for the curfew to begin. After curfew Londoners had to carry a lighted torch or they could be arrested and incarcerated until dawn.

|

| Religion in Medieval London |

All over the city. my characters would hear a constant din from the different crafts that were practised. The noisiest were metalworkers; the blacksmiths, farriers, pewterers, silver and goldsmiths, cutlers and bell founder all used hammers and contributed to the general clamour. I can only compare the activity to that of busy streets in an Indian city or in cities of the Far East.

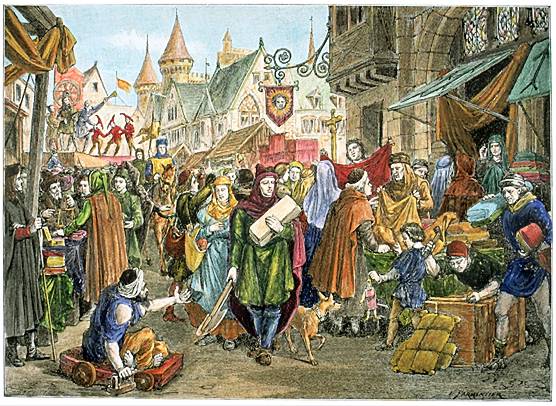

|

| Late Medieval London |

In London there were two hundred fraternities in which craft regulation and religious observation were mingled. Guilds had acquired enormous economic power within the city by the end of the medieval period. The growth of craft guilds in medieval London cannot be distinguished from the parish guilds of the same neighbourhood. thus tanners who worked along the banks of The River Fleet for instance would meet at their fraternity in the Carmelite house in Fleet Street. According to Peter Ackroyd in his book London, three fraternities were recorded at in the church of St Stephen, Coleman Street during the late thirteenth century. By the early fourteenth century only citizens could belong to a trade guild. Aliens were not only foreigners but those who were not London's citizens.

Many tradesmen met for business in the church. Religious and social constraints emphasized the importance of honesty and good behaviour. The guilds had their rules. Good names must be protected and the guilds condemned those who broke public peace. It was as if the act of quarreling or being involved in disputes might be construed as sinful.

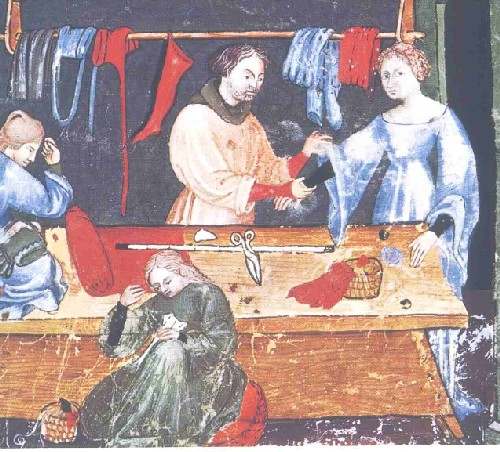

|

| The Baker's Apprentice |

Young people entered apprenticeships in late medieval London able to read and write. They were expected to be honest and to have learned manners. They were to be straight-limbed and free-born. And by the mid fifteenth century the children had to be born in England. Well-born recruits were preferred and parents of apprentices had to have properties bringing in 20s a year. The Lord's daughter, the baker's son, the children of London mercers, vintners or fishmongers were not raised at home for long. All of them were either apprenticed or they became attendants or servants in someone else's household. The best upbringing for a child was to send him out of the family to learn the ways of the world and to be educated elsewhere. Young women were usually apprenticed to silkwomen, dressmakers or embroiderers. There are instances too of girls being apprenticed to butchers, bakers, cordwainers, drapers, grocers, apothecaries and surgeons. They could either remain single and practise as femme soles under London law after they married and actually having a skill was an advantage in the marriage market. The apprentice term would end if marriage were offered and often the apprenticeship was only for four years, not seven, in practise although it was not legal. What a woman's apprenticeship was not, was as a stepping stone to an independent life as a citizen of London.

|

| Medieval Silk women |

.jpg)

_-_WGA24166.jpg)